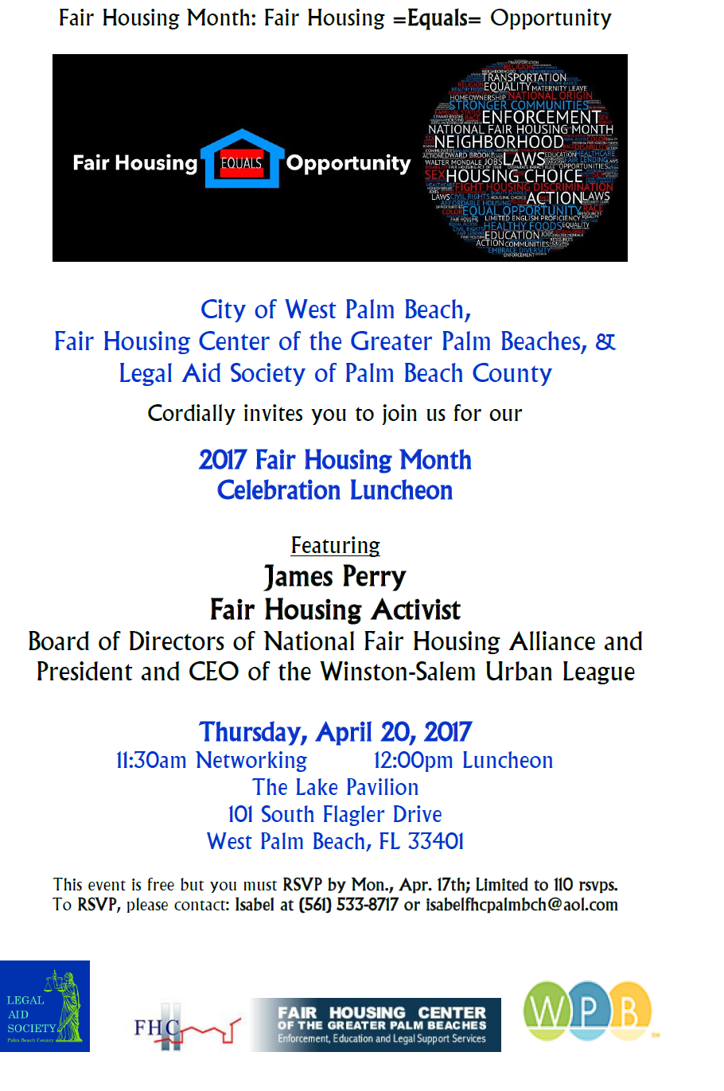

APRIL IS FAIR HOUSING MONTH! Come celebrate Fair Housing Month with us as we welcome you to attend our signature event. See below for more details. RSVP’s are required and due by April 17th. Event & Valet Parking FREE!!!

- At April 10, 2017

- By fhfla

- In News

0

0

FHC FILES HOUSING DISCRIMINATION COMPLAINT WITH THE HUD AGAINST THE CITY OF BOYNTON BEACH FOR DISCRIMINATING AGAINST PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES”

- At April 06, 2017

- By fhfla

- In News

0

0

The Fair Housing Center of the Greater Palm Beaches, Inc. (FHC) has filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) against the City of Boynton Beach (the City). The complaint alleges discrimination based on Handicap/Disability, in violation of the Fair Housing Act and Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act.

On November 5, 2016 the Justice Department and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) released an updated guidance on the application of the federal Fair Housing Act (FHA) to state and local land use and zoning laws. The guidance is designed to help state and local governments better understand how to comply with the FHA when making zoning and land use decisions, as well as to help members of the public understand their rights under the FHA.

On December 6, 2016, the City of Boynton Beach City Commissioners adopted Resolution R16-165, declaring the commencement of a study period related to Respondent CBB zoning and use regulations concerning group homes; and to abate the issuance of any permit for group homes within its city limits until June 4, 2017; and undertake review and revision of the zoning and use regulations as they relate to group housing within the City of Boynton Beach. On December 19, 2016 the City again voted unanimously to institute it’s six month moratorium on all group homes, in violation of Fair Housing Act and Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act.

“Suppose a municipality issued a moratorium barring families with children, Blacks or Latinos from moving to that City, while they study the law. No one would stand for that!” stated Vince Larkins, FHC President & CEO. “The idea that the City of Boynton Beach thinks that they can discriminate against a whole group of people is outrageous. The FHC will not sit idly by while people with disabilities are targeted, in violation of federal Fair Housing Act”, he further stated.

Group homes cover a wide range of disabilities. Residents usually have some type of chronic mental disorder that impairs their ability to live independently. Many residents also have physical disabilities such as impairments of vision communication, or ambulation.

Statement from Lisa Rice, Executive Vice President of the National Fair Housing Alliance on the Confirmation of Dr. Ben Carson as Secretary of HUD

- At March 16, 2017

- By fhfla

- In News

0

0

The National Fair Housing Alliance strongly urges Dr. Ben Carson, in his new role as Secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, to tackle immediately the many critical housing challenges that our country faces. Many of these are a legacy of the financial and foreclosure crises which disproportionately impacted America’s communities of color. These communities have yet to recover. Housing inequality has had a devastating effect on individuals, communities and businesses and HUD plays a pivotal role in eliminating this inequality. The National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA) and its members across the country invite Secretary Carson to work with us to address these pressing issues.

Housing discrimination continues to be a significant problem in this country, unfairly limiting people’s choices about where to live. NFHA estimates that more than 4 million instances of housing discrimination occur annually.During his confirmation hearing, Secretary Carson said he would “aggressively enforce the Fair Housing Act,” and referred to the law as, “one of the best pieces of legislation which we’ve had.”